Eggcorn Forum

Discussions about eggcorns and related topics

You are not logged in.

Announcement

The Eggcorn Forum and the Eggcorn Database are currently in the process of being converted into static sites.

Once the conversion is complete, all existing posts are expected to still be accessible at their original URLs. However, no new posts will be possible.

Feel free to comment on the relevant forum threads.

Chris -- 2025-05-10

#1 2009-06-05 22:12:50

- DavidTuggy

- Eggcornista

- From: Mexico

- Registered: 2007-10-11

- Posts: 2767

- Website

-er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

I had written:

Not to start another long discussion, but – er has a lot in common with the sound-symbolic quasi-morphemic whatchamacallems

kem replied:

That wouldn’t be me you are referring to, would it? ¶ Nuttin’ wrong with morphemic ”-er” and ”-el/le.” Any diachronic understanding of English grammar would recognize the morphological independence of these suffixes. ¶ For frequentative ”-er” the OED cites batter, chatter, clamber, flicker, glitter, mutter, patter, quaver, shimmer, shudder, slumber. Your list adds a few more (“Fritter” probably does not belong in the list. Too bad. “Frit” would make such a good Teutonic root. I can imagine it meaning “to carve into thin slices, especially roasted boars and captured Romans.”). ¶ For frequentative/diminutive ”-el/le” the OED has nestle, twinkle, wrestle, crackle, crumple, dazzle, hobble, niggle, paddle, sparkle, topple, wriggle, babble, cackle, gabble, giggle, guggle, mumble.

No examples in the OED list where it’s spelt -el? Grovel, pummel, snivel what else? Anyway, I’ve had fun making up longish lists of these since 30 years and more ago, along with oddities that may well be related [e.g. nouns like handle, pestle, sickle, shovel, nipple that denote instruments for often repetitive tasks, or for things naturally occurring in groups like freckle, thunder, rubble, gaggle .]

.

You accept these as full-fledged morphemes but deny that status to things like the fl- of flutter, flicker, flip, flop, flap, flash, fling etc. You’re in good company of course—there are lots of linguists eager to exclude these things from their morphology because they wreak havoc with their nice morphemic principles if for no other reason. We have agreed that if they are morphemes they are a peripheral kind.

.

I think – le and especially – er ‘repetitive/frequentative’ edge towards the same part of the periphery. The following are some important similarities between fl- and – er:

.

(1) Speakers are not highly aware of them as separable morphemes. Few would spontaneously divide batter into bat + er , for instance.

.

(2) If they are morphemes they are certainly not stems: they cannot occur by themselves. In this respect they are affixal.

.

(3) However, if they are removed from a word what remains is typically not an independently established stem. (In the case of fl it may never be, and this may be the defining characteristic of the sound-symbolic thingies.) E.g. mut (cf. mutter ) doesn’t mean anything by itself. This is not true of more typical affixes (e.g. – s ‘3rd person sg subj present tense’.)

.

(4) Some aspects of them and the words they form approach some kind of onomatopoeia or other iconicity. (E.g. the fluttering of the tongue in pronouncing flutter or the muttering in pronouncing mutter, mumble .)

.

(5) The sound that constitutes their phonological pole doesn’t in all cases bear the meaning. (E.g. laser, finger, mother, Easter, under, and all the thousands of cases with the multi-polysemous nominalizer – er as in rocker, drawer, trailer, ruler, computer, Britisher, nor’easter, grounder, beaker don’t seem to include a salient repetitive or frequentative meaning.) In other words, the sound meaning association is far from absolute . (This absence is what you first commented on, Ken, as somehow indicating that the sound-symbolic thingies weren’t real morphology.)

.

(6) The meanings are quite schematic (=vague, easily applicable in varying degrees to different concepts). (This is typical of affixes, for fairly obvious reasons.)

.

(7) The results of applying them are likely to be surprising/unpredictable in some degree. In this (and other) ways they are derivational rather than inflectional affixes.

.

(8) They are far from freely productive: new forms using them are not commonly formed and not necessarily readily understood. (E.g. why don’t we say drobble, slizzle, chobble , or other reasonable forms of that sort?)

.

(9) There’s some interesting phonology associated with them that is not general in English. (E.g. )

.

I’m sure I’m leaving a few things out, but it’s late, and I’m shambling/staggering off to flop/fling myself into bed.

*If the human mind were simple enough for us to understand,

we would be too simple-minded to understand it* .

Offline

#2 2009-06-06 13:19:46

- kem

- Eggcornista

- From: Victoria, BC

- Registered: 2007-08-28

- Posts: 2887

Re: -er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

David-

I think we agreed before that the substance of our discussion revolved around the meaning we attached to “morpheme.â€

I see morphemic status lying along a spectrum. On the one end is the claim that every sound contributes to meaning. Some sounds contribute more, some less, of course. Even if we could locate that rare bird, the sound that had no meaning, it would quickly gain a meaning-as soon as a language community began to employ the sound, someone would use it to make differences in meaning. Call this position the left end of the spectrum.

The other end of the spectrum is the dictionary end. On this end we let the modern dictionary, as the lexigraphical art is currently practiced, determine the morphemes of our language. Only words in the dictionary have meanings. Call this the right end.

I find myself more or less in the middle of this spectrum. I agree with those on the left that there are adfixes and even a few infixes that have definable semantic components. There are multiword units that act as unitary morphemes. Even some onomatopoetic sounds function as morphemes. But I also agree with those on the right that there are sounds that are not morphemes. To be a morpheme a sound has to play some role, historical or contemporary, in syntax and/or grammatical inflections in a language. The sound has to carry its meaning consistently across the range of its use in ways that can be statistically analyzed. In short, there has to be some semi-scientific way of defining what is and is not a morpheme.

As for frequentative “-er,†I would let it stand as an English morpheme simply because it did strong morphemic stuff at one point in the history of the language. Whether or not it is still a morpheme for a significant group of speakers, however, is an open question. English has become a lake into which many “-er†morphemes flow. The OED, for example, has six separate entries for “-er, suffix,†each with a different etymological source. Every new â€-er†stream dilutes the English lake a little, making it harder for speakers using an “-er†suffix to get listeners to focus on the right one. I suspect that it is no longer possible to coin a new verb with a frequentative “-er†and have a listener divine your intention. Keeping it as an English morpheme helps me to understand the spelling and history of some English words that are still in use, however, so I’m not ready to let it slip into the fuzz on the left side of the spectrum.

Hatching new language, one eggcorn at a time.

Offline

#3 2009-06-06 20:07:21

- patschwieterman

- Administrator

- From: California

- Registered: 2005-10-25

- Posts: 1680

Re: -er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

I probably shouldn’t say anything because I’m about to go out of internet range for most of a week, but sound symbolism is a topic that’s long interested me so I’ve got to say a little here.

Kem—Your last paragraph seems to imply that only productive morphemes are morphemes—which may not be what you actually intended to say. Lots of legitimate, card-carrying morphemes are no longer productive.

Also, many linguists who write on sound symbolism acknowledge that phonemic clusters like “fl-” may not fulfill all the usual criteria of “morphemes,” but that doesn’t seem to constitute for them a major stumbling-block to belief in the larger concept; such clusters are sometimes referred to as “submorphemic” elements (or even “phonesthemes”) by people writing on sound symbolism/phonesthesia.

In Steven Pinker’s recent book The Stuff of Thought, he lumps together “le for aggregates of small objects” (pebble, stubble, etc.) with “gl- for emission of light” (glare, glitter, etc.), “j- for sudden motion” (jump, jab, etc.), and “cl- for a cohesive aggregate or a pair of surfaces in contact” (clam, clamp, etc.). He calls these clusters a part of the phenomenon of phonesthesia, in which “”families of words share a teeny snatch of sound and a teeny shred of meaning” (p. 301). I couldn’t help but wonder whether he wasn’t avoiding the word “morpheme” (discussed much earlier in the book) in that sentence precisely because of the problem of defining these things within the terms of traditional morphology. Nevertheless, that doesn’t prevent him from implicitly endorsing the idea.

Last edited by patschwieterman (2009-06-06 20:27:55)

Offline

#4 2009-06-29 17:40:44

- kem

- Eggcornista

- From: Victoria, BC

- Registered: 2007-08-28

- Posts: 2887

Re: -er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

Thanks, Pat, for giving us a handle. “Phonesthesia,” it turns out, is a convenient term for looking up some of the discussion and debate on the topic of sound symbolism. By using it as a search term, I located a helpful paper by Benjamin Shisler at http://www.geocities.com/SoHo/Studios/9 … npap1.html .

Critical studies in phonesthetics often lack a sense of what constitutes meaningful argument. In order to make useful claims, we need more than a grab bag of words that share a sound and meaning. If I argue (just to make up an example) that the initial /t/ sound indicates a combination of science and mechanical skill because it occurs in the words “technology,†“train,†“television,†“typewriter†and “tool,†and I write a paper about it and get ten people to agree with me, have I really said anything meaningful? The arguments advanced in some phonesthetics papers remind me of the sentence that W. H. Auden (Foreword to Owen Barfield’s History in English Words) puts in the mouth of a hypothetical Frenchman: “The great advantage of the French language is that in it the words occur in the order in which one thinks them.” If we presuppose that everyone thinks in French, the French language is obviously the best one to use. If we presuppose that correlations between English symbols and sounds are morphemes a-borning, we can find morphemes and protomorphemes everywhere we look. I am more comfortable with an arbitrary relationship between sound and symbol as the gold standard. Non-accidental connections are allowed only in special cases, ones for which we have some hard evidence that sounds and symbols are linked, such as such as onomatopoeic words and historical morphemes.

Plato stands as a negative example of where phonesthetic thoughts can lead. Several sections of his dialogue Cratylus anticipate some ideas of sound symbols. Here, from Benjamin Jowett’s translation (http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/6/1/161 … 1616-h.htm) is Socrates at his most absurd:

SOCRATES: My first notions of original names are truly wild and ridiculous, though I have no objection to impart them to you if you desire, and I hope that you will communicate to me in return anything better which you may have.

.

HERMOGENES: Fear not; I will do my best.

.

SOCRATES: In the first place, the letter rho appears to me to be the general instrument expressing all motion (kinesis)..... Now the letter rho, as I was saying, appeared to the imposer of names an excellent instrument for the expression of motion; and he frequently uses the letter for this purpose: for example, in the actual words rein and roe he represents motion by rho; also in the words tromos (trembling), trachus (rugged); and again, in words such as krouein (strike), thrauein (crush), ereikein (bruise), thruptein (break), kermatixein (crumble), rumbein (whirl): of all these sorts of movements he generally finds an expression in the letter R, because, as I imagine, he had observed that the tongue was most agitated and least at rest in the pronunciation of this letter, which he therefore used in order to express motion, just as by the letter iota he expresses the subtle elements which pass through all things. This is why he uses the letter iota as imitative of motion, ienai, iesthai. And there is another class of letters, phi, psi, sigma, and xi, of which the pronunciation is accompanied by great expenditure of breath; these are used in the imitation of such notions as psuchron (shivering), xeon (seething), seiesthai, (to be shaken), seismos (shock), and are always introduced by the giver of names when he wants to imitate what is phusodes (windy). He seems to have thought that the closing and pressure of the tongue in the utterance of delta and tau was expressive of binding and rest in a place: he further observed the liquid movement of lambda, in the pronunciation of which the tongue slips, and in this he found the expression of smoothness, as in leios (level), and in the word oliothanein (to slip) itself, liparon (sleek), in the word kollodes (gluey), and the like: the heavier sound of gamma detained the slipping tongue, and the union of the two gave the notion of a glutinous clammy nature, as in glischros, glukus, gloiodes. The nu he observed to be sounded from within, and therefore to have a notion of inwardness; hence he introduced the sound in endos and entos: alpha he assigned to the expression of size, and nu of length, because they are great letters: omicron was the sign of roundness, and therefore there is plenty of omicron mixed up in the word goggulon (round). Thus did the legislator, reducing all things into letters and syllables, and impressing on them names and signs, and out of them by imitation compounding other signs. That is my view, Hermogenes, of the truth of names….

The claims of the phonethesiasts don’t take this train as far as Socrates did. But the train is heading in the direction that Socrates is going, and it is not clear to me where the stations are that let us get off this “wild and ridiculous†line of thought.

Hatching new language, one eggcorn at a time.

Offline

#5 2009-06-30 00:52:15

- patschwieterman

- Administrator

- From: California

- Registered: 2005-10-25

- Posts: 1680

Re: -er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

I like “phonesthesiasts”—a googlenope so far, but this thread probably guarantees that that will change.

Kem wrote:

Critical studies in phonesthetics often lack a sense of what constitutes meaningful argument.

Kem, whose work in particular are you objecting to?

Offline

#6 2009-06-30 12:50:43

- kem

- Eggcornista

- From: Victoria, BC

- Registered: 2007-08-28

- Posts: 2887

Re: -er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

I wasn’t reading the studies so much as I was reading about them.

But if you want a sample author, take a look at the work of Margaret Magnus, who did a Ph.D. in sound symbolism. Her pages are at http://www.trismegistos.com/MagicalLetterPage/ The perspectives on English sound and meaning on these pages reproduce Socrates’ take on Attic Greek.

The methodological problems with the studies on the Magnus pages boil down to two problems: sampling bias (semantic categories are selected with the data set in mind) and correlation/causality. Conceptual problems add to the confusion-chiefly, the use of “meaning” and “morpheme” in senses so broad that they lose almost all their historical moorings.

Hatching new language, one eggcorn at a time.

Offline

#7 2009-06-30 14:05:35

- patschwieterman

- Administrator

- From: California

- Registered: 2005-10-25

- Posts: 1680

Re: -er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

I don’t feel Margaret Magnus is a very good example of work being done on sound symbolism in linguistics. As far as I know, she doesn’t hold a PhD—she did doctoral work in linguistics at MIT in the early 80s, but left without filing a thesis. Though I couldn’t find a reference just now, I’ve read before that she’s worked at universities—but as a computational analyst (I think) rather than as someone with a teaching position in linguistics. And she’s had a successful career with consulting firms that create names and brand-names for high-powered companies.

I’ve only seen her book referenced once in a recent article on sound symbolism, and it was included in a list of methodologically problematic approaches to the concept. (I don’t want to make it sound like I’ve read widely in the discipline of sound symbolism—probably fewer than a dozen articles in the last 2-3 years, so I’m not intending to claim here a very well-informed sense of what’s out there.) I flipped through her book, and, yes, I didn’t bother to read more or check it out of the library because it looked sketchy to me, too. However, I do think she offers a useful challenge to mainstream linguists to incorporate computational approaches more regularly into the study of sound symbolism.

But I think any branch of modern linguistics needs to be judged by the work of degreed linguists publishing in refereed journals well regarded in the field. And these days there appear to be plenty of such people. The volume that really changed a lot of minds about sound symbolism was the 1994 collection Sound Symbolism that came out on Cambridge UP. It was edited by Leanne Hinton, John J. Ohala and Johanna Nichols. I’m unfamiliar with Nichols, but Hinton and Ohala are well-known names in linguistics (as are a number of other contributors—though one of the striking features of the book is the range of disciplines from which the contributors are drawn). The book has been widely cited, and is probably the main reason for the gradual “mainstreaming” of studies of sound symbolism in the last 10-15 years. I doubt Stephen Pinker, for instance, would be casually discussing phonesthesia, etc. in his popularizing treatments if this work had never existed. And one quick way to find more recent work by professional linguists working in the discipline is to go to scholar.google.com, put in the Hinton volume, and then start following links among the 114 listed works that cite it. I’ve seen plenty I’ve found unconvincing in the little I’ve read in the Hinton book or in linguistics journals (as well as plenty that was interesting and stimulating), but I haven’t yet read a study that could be reduced to “a grab bag of words that share a sound and meaning.”

[Edit: After posting this, I wondered whether I could find a resume for Magnus online. Yes—it’s here: http://www.trismegistos.com/MagicalLett … sume.html. And she does indeed have a PhD—a couple of years after the publication of her book, she completed the degree at the University of Trondheim in Norway.]

Last edited by patschwieterman (2009-06-30 14:26:40)

Offline

#8 2009-06-30 16:08:14

- kem

- Eggcornista

- From: Victoria, BC

- Registered: 2007-08-28

- Posts: 2887

Re: -er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

Thanks for the reference. Our local university library has the Hinton volume. I’ll take a look at it.

I suspect that I’ll agree with much of what’s in the Sound Symbolism book. I don’t have any large, programmatic disagreement with sound symbolism-as I said earlier, I’d put myself in the middle of the spectrum. Here, for example, is an academic study of sound symbolism in nicknames that seems to me to do a lot of its investigation in the right way (Nicknames, when you think about it, are a good place to look for sound symbolism-the peculiar semantics of names opens the door for phonetic influences on meaning.). But when I look at approaches to sound symbolism like that in the Magnus books, the little troll inside me, the one that I nursed all those years that I did philosophy and logic, starts yammering away, and I can’t seem to make it shut up.

Disagreements over the extent and significance of sound symbolistic phenomena, as I’m sure you’re aware, go back a long way in linguistics. We’re probably recapitulating discussions that have happened many times over the last century. See, for examples, the disagreements between Firth and Jespersen in Robin Allott’s 1995 article on “Sound Symbolism.”

Last edited by kem (2009-12-31 21:15:57)

Hatching new language, one eggcorn at a time.

Offline

#9 2013-04-05 15:37:50

- kem

- Eggcornista

- From: Victoria, BC

- Registered: 2007-08-28

- Posts: 2887

Re: -er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

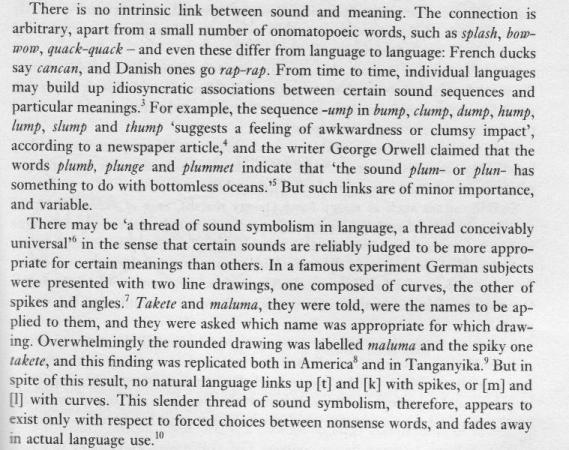

I just read Jean Aitchison’s book Words in the Mind (2nd ed). She weighs in on sound symbolism issues in her last chapter:

Hatching new language, one eggcorn at a time.

Offline

#10 2013-04-06 07:42:05

- JuanTwoThree

- Eggcornista

- From: Spain

- Registered: 2009-08-15

- Posts: 455

Re: -er and -le/el ‘frequentative’ and quasi-morphemes

all the thousands of cases with the multi-polysemous nominalizer – er as in rocker, drawer, trailer, ruler, computer, Britisher, nor’easter, grounder, beaker don’t seem to include a salient repetitive or frequentative meaning.

I’m not so sure. I have been known to rock, but I’m a long way from being a rocker. I am a teacher though.

On the plain in Spain where it mainly rains.

Offline